Java Man Returns Home Confused

Prologue

“Oh, god. Have I been using the wrong language all these years?”

Introduction

I have earlier implemented the same simple REST server using Javascript/Node and Clojure for educational purposes to learn those languages, (see my previous blog posts:

- Clojure: Become a Full Stack Developer with Clojure and ClojureScript!

- Javascript/Node: Java Man’s Unholy Quest in the Node Land

Now I implemented the same web server using Java. I have been programming Java for some 20 years, so I didn’t do this exercise to learn Java. I mainly wanted to implement the Simple Server using Java just to compare the Java implementation with Javascript/Node and Clojure implementations. Actually it has been quite fun to implement the exact same functionality using three different languages — you get a funny deja vu feeling and can really compare the different languages when you have used them to implement the exactly same thing (something you never can do in corporate life).

You can find the project in Github.

Once again I tried to replicate the file/namespace/class names so that it is easy to compare the implementations (e.g. server.js — server.clj — Server.java ).

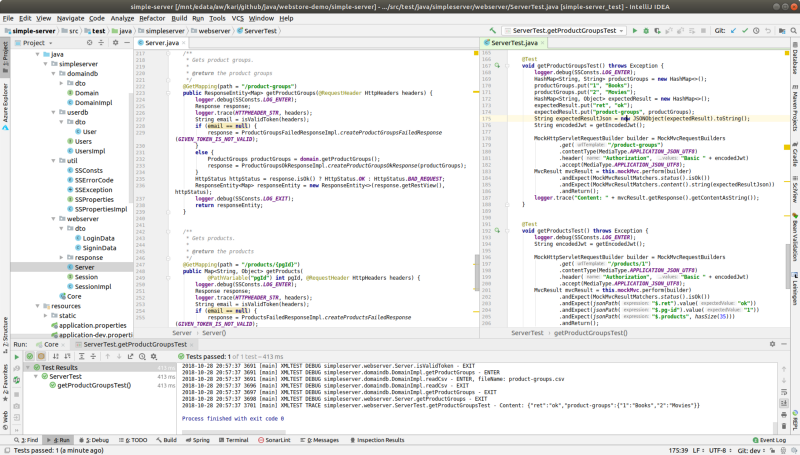

IntelliJ IDEA hacking session running server unit tests.

Spring Boot 2.0 and Spring 5.0

I remember back in mid 2000 when Java EE was really bloated and pretty awkward to use with all application server and EJB hassle, and Spring Framework came with its dependency injection and autowiring and made things easier. Well, Spring itself seems to be rather bloated nowadays and therefore we have Spring Boot which considerably makes building Spring applications easier.

Simple Server is implemented using Spring Boot v. 2.0.5 which uses Spring Framework v. 5.0.9 (see Spring Boot Documentation — Appendix F. Dependency versions.

Spring makes things easier but it also causes quite a lot of issues. E.g. if you just forget one annotation you may spend a couple of hours figuring out why some property is not injected properly. In Spring if everything is configured properly you are good to go. If not, then it is at times pretty frustrating to find the root cause inside Spring autowiring and other magic. I rarely had this kind of configuration issues with Clojure or Python.

IntelliJ IDEA

IntelliJ IDEA is my favorite Java IDE. I used for years Eclipse since it is free and very widely used with our offshore developers (and I was working as an onsite architect at that time — clear benefits to use the same IDE and provide examples for developers using the common IDE — using the same IDE is not so important any more). I switched a few years ago to IntelliJ IDEA and have never missed bloated Eclipse ever since. I use PyCharm for Python programming and since PyCharm and IDEA are provided by the same company (JetBrains) they provide very similar look-and-feel. I also use IntelliJ IDEA with Cursive plugin for Clojure programming and it also provides very similar look-and-feel. For my previous Javascript exercise I used Visual Studio Code (and with my personal tweakings I managed to make it give pretty same feel, though the look is different, of course).

Java REPL

Java 9 introduced a shiny Java REPL! This is nothing compared to Lisp REPLs but anyway it’s nice to have a Java REPL at last. You can start a Java REPL session in console with command “jshell”.

IntelliJ IDEA also implements a nice Java REPL integration and it is actually a lot easier to use JShell with IDEA than in console. IDEA REPL is able to load all your dependencies to the JShell (also application classes), and the REPL editor is pretty nice (with code completion capabilities).

An example to experiment JSON Web Token creation and parsing in IDEA REPL:

import io.jsonwebtoken.Jwts;

import io.jsonwebtoken.SignatureAlgorithm;

import io.jsonwebtoken.security.Keys;

import java.security.Key;

Key key = Keys.secretKeyFor(SignatureAlgorithm.HS256);

String jws = Jwts.builder().setSubject("Jamppa").signWith(key).compact();

String name = Jwts.parser().setSigningKey(key).parseClaimsJws(jws).getBody().getSubject();Run the code snippet in REPL and the JShell console replies:

import io.jsonwebtoken.Jwts

import io.jsonwebtoken.SignatureAlgorithm

import io.jsonwebtoken.security.Keys

import java.security.Key

field Key key = javax.crypto.spec.SecretKeySpec@5883e04

field String jws = "eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiJ9.eyJzdWIiOiJKYW1wcGEifQ.PjF1ilMY_iq96wTE8ptDRH_zGaIrTU-mYmjy3SZmnos"

field String name = "Jamppa"

Pretty nice? And how long did we have to wait for the Java REPL? Just some 20 years? But remember: This is just a code snippet REPL like Python or Node REPL, not a real REPL like a Lisp REPL, e.g. a Clojure REPL (see e.g. Programming at the REPL: Introduction). With a real Lisp REPL you can interact with the real program as it is and explore the program in a way no code snippet REPL or debugger can do. It’s pretty impossible to explain it, you just have to learn Lisp (e.g. Clojure) and try it out.

JUnit5

Latest Spring Boot that I used when writing this blog article was version 2.0.5 which comes with JUnit 4.12. There were major changes in the new JUnit5 and I wanted to try those, so I configured build.gradle to use JUnit5.

Using JUnit5 it is pretty nice to test e.g. exceptions:

// Trying to add the same email again.

Executable codeToTest = () -> {

User failedUser = users.addUser("jamppa.jamppanen@foo.com", "Jamppa", "Jamppanen", "JampanSalasana");

};

SSException ex = assertThrows(SSException.class, codeToTest);

assertEquals("Email already exists: jamppa.jamppanen@foo.com", ex.getMessage());

The automated unit tests take considerably more time in Java and Clojure than in Javascript/Node (because OS loads JVM, and JVM loads application and test classes and only then JVM lets testing framework to start the actual testing…):

Java:

$ time ./gradlew --rerun-tasks test

Test result: SUCCESS

Test summary: 15 tests, 15 succeeded, 0 failed, 0 skipped

BUILD SUCCESSFUL in 5s

5 actionable tasks: 5 executed

real 0m5.757s

Javascript/Node:

time ./run-tests-with-trace.sh

28 passing (94ms)

real 0m0.775sJavascript: 0.8 secs — Java: 5.8 secs.

Doesn’t look good for Java.

Java Verbosity

Let’s have an example of Java verbosity and complexity related to other languages I used to implement the Simple Server.

Here we test API /product-groups which returns a simple JSON map. See how complex the testing is to implement in Java:

Java:

@Test

void getProductsTest() throws Exception {

logger.debug(SSConsts.LOG_ENTER);

String encodedJwt = getEncodedJwt();

MockHttpServletRequestBuilder builder = MockMvcRequestBuilders

.get("/products/1")

.contentType(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON_UTF8)

.header("Authorization", "Basic " + encodedJwt)

.accept(MediaType.APPLICATION_JSON_UTF8);

MvcResult mvcResult = this.mockMvc.perform(builder)

.andExpect(MockMvcResultMatchers.status().isOk())

.andExpect(jsonPath("$.ret").value("ok"))

.andExpect(jsonPath("$.pg-id").value("1"))

.andExpect(jsonPath("$.products", hasSize(35)))

.andReturn();

logger.trace("Content: " + mvcResult.getResponse().getContentAsString());

logger.debug(SSConsts.LOG_EXIT);

}

The same in Clojure:

(deftest get-product-groups-test

(log/debug "ENTER get-product-groups-test")

(testing "GET: /product-groups"

(let [req-body {:email "kari.karttinen@foo.com", :password "Kari"}

login-ret (-call-request ws/app-routes "/login" :post nil req-body)

dummy (log/debug (str "Got login-ret: " login-ret))

login-body (:body login-ret)

json-web-token (:json-web-token login-body)

params (-create-basic-authentication json-web-token)

get-ret (-call-request ws/app-routes "/product-groups" :get params nil)

dummy (log/debug (str "Got body: " get-ret))

status (:status get-ret)

body (:body get-ret)

right-body {:ret :ok, :product-groups {"1" "Books", "2" "Movies"}}

]

(is (= (not (nil? json-web-token)) true))

(is (= status 200))

(is (= body right-body)))))

… and Javascript:

describe('GET /product-groups', function () {

let jwt;

it('Get Json web token', async () => {

// Async example in which we wait for the Promise to be

// ready (that i.e. the post to get jwt has been processed).

const jsonWebToken = await getJsonWebToken();

logger.trace('Got jsonWebToken: ', jsonWebToken);

assert.equal(jsonWebToken.length > 20, true);

jwt = jsonWebToken;

});

it('Successful GET: /product-groups', function (done) {

logger.trace('Using jwt: ', jwt);

const authStr = createAuthStr(jwt);

supertest(webServer)

.get('/product-groups')

.set('Accept', 'application/json')

.set('Authorization', authStr)

.expect('Content-Type', /json/)

.expect(200, {

ret: 'ok',

'product-groups': { 1: 'Books', 2: 'Movies' }

}, done);

});

});

As you can see from the example in Clojure and Javascript we can treat data as data, in Java not so much. In Java if you want to create Java-ish code you have to implement class this and class that for your data. In Clojure you can just use Clojure native data structures in code, and in Javascript JSON data structures, which makes much more sense and makes the code more readable as well. (Now some Java wise guy might want to comment to this blog that “you could have populated the JSON as string, something like “{ 1: ‘Books’, 2: ‘Movies’ }” — yes, you can do that but you miss my point: in Javascript and Clojure you can represent the data inside the program using native data structures, not Java classes or Strings).

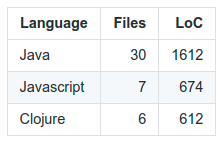

Let’s also compare the lines of code between these three languages:

Java:

$ find src/main/ -name "*.java" | xargs wc -l

108 src/main/java/simpleserver/userdb/UsersImpl.java

50 src/main/java/simpleserver/userdb/Users.java

36 src/main/java/simpleserver/userdb/dto/User.java

156 src/main/java/simpleserver/domaindb/DomainImpl.java

34 src/main/java/simpleserver/domaindb/dto/ProductGroups.java

23 src/main/java/simpleserver/domaindb/dto/Info.java

47 src/main/java/simpleserver/domaindb/dto/Product.java

45 src/main/java/simpleserver/domaindb/Domain.java

21 src/main/java/simpleserver/util/SSErrorCode.java

11 src/main/java/simpleserver/util/SSConsts.java

19 src/main/java/simpleserver/util/SSProperties.java

29 src/main/java/simpleserver/util/SSPropertiesImpl.java

70 src/main/java/simpleserver/util/SSException.java

29 src/main/java/simpleserver/webserver/Session.java

289 src/main/java/simpleserver/webserver/Server.java

23 src/main/java/simpleserver/webserver/response/Response.java

... and some 14 more classes ...

1612 total

Javascript:

$ find src -name "*.js" | xargs wc -l

126 src/userdb/users.js

108 src/domaindb/domain.js

10 src/core.js

33 src/util/prop.js

29 src/util/logger.js

79 src/webserver/session.js

289 src/webserver/server.js

674 total

Clojure:

$ find src -name "*.clj" | xargs wc -l

65 src/simpleserver/userdb/users.clj

36 src/simpleserver/core.clj

80 src/simpleserver/domaindb/domain.clj

99 src/simpleserver/util/prop.clj

89 src/simpleserver/webserver/session.clj

243 src/simpleserver/webserver/server.clj

612 total

And the results in table format:

So, it’s pretty clear that dynamic languages are easier to work with.

Conclusions

Spring and Spring Boot

Spring Boot makes creating server / microservice applications using Java much easier. Spring provides a great framework which glues your components together. It’s hard to find a reason not to use Spring (i.e. to create a pure EE Java app). I guess hardly no-one nowadays uses pure EE.

But remember: if you want to deviate from the default Spring Boot configuration (as I did when I used JUnit5 instead of JUnit4) you are pretty soon googling why some autowiring or servlet context or something is not working as it should.

Java as a Language

Some comments regarding Java as a language:

Verbosity. Java is really, really verbose if you compare it to dynamic languages like Python, Javascript or Clojure. If you want to create a Java-ish solution you are implementing class this and class that. For almost any data you implement a new class. Why data can’t just be — data?

Object oriented paradigm. Object oriented paradigm was something cool in mid 1990’s but nowadays seems more or less an unholy mess of classes having data, method and other classes having other data, methods and other classes… For data oriented applications I would rather use functional paradigm which makes a better separation between data and functions that operate on data.

Getters and Setters. For simple data classes in which the fields are the interface it is stupid to make the fields private and provide a huge list of getters and setters. In those cases I think it is better just to make the fields public. If there is a reason to hide some internal structure, then you should make that field private, of course. The getters/setters is definitely something that was not properly designed in the Java language.

Checked exceptions. Another (possible) design flaw was the checked exceptions which some consider as a failed experiment in the language. If you use checked exceptions you should understand to use them only in those situations in which you want to enforce the calling code to deal with a possible exception and the calling code really can do something about it.

Safety. If you need a statically typed safe language and runtime environment (JVM — some 20 years of solid testing in enterprise world) with a great ecosystem for a big enterprise project with tens of developers — Java is the solution.

IDE tooling. IDE tooling is of course great since we are using statically typed language. IntelliJ IDEA (my favorite Java IDE) provides exact suggestions for methods when it recognizes which class we are dealing with.

Learning curve. A bit difficult to say something about this since I’ve been programming Java some 20 years now (first Java project was actually in year 1998). But after this exercise I have a feeling that for a newbie programmer Java basic stuff cannot be learned in a couple of days and then start being productive and learn the new stuff on the way as you can do e.g. with Python and Javascript. Also the frameworks take some time to learn (even a hard-core Java programmer like me forgot some peculiarities regarding Spring when I have not done serious Java/Spring programming about in 1,5 years). I think it is a lot easier for a Java guy to start using Javascript or Python than a Javascript guy start using Java. Now after implementing the same web server using Javascript/Node and Java I can better understand why those Javascript guys despise Java so much — Java is far from Javascript/Node in developer productivity. But you don’t have to leave JVM for Java’s sins — you can start using Clojure and get the best of both worlds — a battle tested runtime (JVM) with a great functional and immutable language (Clojure).

Rigidness. I’m pretty seasoned Java programmer. But even I myself was quite amazed regarding the productivity between Javascript/Node vs Java. Just for curiosity I looked my Github commits regarding the Javascript/Node implementation of this server exercise, and Java commits: I did both implementations in some 3 weeks (only evenings, not every evening). So, how is it possible that you implement the same server in about the same time with a language you just learned on the fly while implementing the server compared to a language you have used 20 years? Wtf? Have I really used such a non-productive language all these years? I think one of the main reasons for this low productivity is that Java is so verbose and rigid. You have to implement class this and class that to make even minor functionality (if you want to make the implementation Java-ish). In the Javascript, Python and Clojure side you have a lot more freedom because the languages are dynamically typed and you can treat data as data and not as an unholy mix of classes with data and references to other classes.

Summa summarum. Ok, ok, I have been hitting Java with a stick in this chapter but after all Java is not that bad if you use it in the right project. There are also a lot of pros in Java: type safety, great ecosystem, JVM is battle tested runtime, great tooling, a huge developer pool etc. All these reasons make Java a great enterprise language for big critical enterprise projects when many developers need to work on the same code base. But the price is a verbose and rigid language with a rather slow development cycle. E.g. programming in Java really requires TDD so that you can easily develop your system in small increments when you use a good unit/integration test as a development bench (and you get a test suite as a by-product) — not a bad thing per se. Something you don’t need e.g. in Clojure because you have a real Lisp REPL and you can grow your system in a more organic way with the REPL (but you still can create a good test suite, and of course you should).

Epilogue

In the beginning of this story I asked myself: “Have I been using the wrong language all these years?” Well, the answer is: yes and no. “No” in that sense that 20 years ago Java was really something new. You had an enterprise language with garbage collection, which was really good since most of the C / C++ programmers really never learned memory management properly. In those days there were not that much of a choice since customers wanted the projects to be implemented using Java, and Java we used. “Yes”, in that sense that nowadays we have so much more choices. You really don’t have to use Java for small microservice type applications. And I wouldn’t use Java in those kind of small projects unless the customer required so. It is much better to implement small microservices using dynamic productive languages like Javascript/Node, Python or Clojure. And for data oriented projects I would use Clojure since Clojure really shines with data processing (and you can experiment with the live system using REPL so many ways). I would use Java only in some really, really big projects with a lot of developers working on the same code base, so that the static language protects developers from trivial errors assuming something about the parameters and return types.

All right. My homecoming to Java land was rather short, and next I will move to Python land, and then to Go land. Let’s see what kind of reflections those languages will give when comparing the experiences to the languages I already have used to implement the Simple Server.